The final full day of our tour of Japan was in Nagasaki. Before we visited the somber sites of the atomic bombing of this city, we took a cable car to Mount Inasa for a panoramic view of the city.

That’s our ship in the picture (beside my husband’s shoulder) in the Port of Nagasaki. It was worth the five-minute ride on the hot, crowded ropeway (what the Japanese call a cable car) to get a view of the mountains and coastline here.

Most of our time in Nagasaki was spent touring the area where the second atomic bomb detonated near the end of World War II on August 9, 1945. The Peace Memorial Park was constructed here in 1955, ten years after the atomic explosion, and contains quite a few statues to commemorate the victims of the bomb and promote world peace.

Probably the most famous is the Prayer Monument for Peace. This large bronze statue dominates the park. The statue’s right hand pointing up symbolizes the threat of the atomic bomb. The left hand stretched horizontally is asking for peace. The closed eyes are in prayer for the victims of war.

The Nagasaki Bell was erected to mark the city as the last to be hit by an atomic bomb. A sign there says “…we pray that peace will spread throughout the world in concentric circles from our city with the ringing of the Nagasaki Bell….” The bell is also a tribute to students who perished from the blast as they worked in Nagasaki factories, taking the places of men who were away at war.

When the atomic bomb exploded, thousands of Nagasaki residents suffered horrific burns and died begging for water. The Fountain of Peace is dedicated as an offering of water to these victims. It’s interesting to see that the fountain sprays are in the shape of a pair of wings, symbolizing the dove of peace.

The bomb detonated approximately 1,600 feet above this monolith, which was constructed to mark the spot. Out of the city’s population of about 240,000 at the time, 73,884 were killed and 74,909 injured. Others died later from radiation poisoning. The black box in front of the monolith contains the names of those who perished as a result of the atomic bomb.

The Urakami Cathedral, the largest Christian church in East Asia at the time, was leveled by the blast. The church’s twin 85-feet high spires were blown down but reconstructed as a testimony of survival.

A branch of the Nagasaki Prison was the closest public building to the hypocenter. The prison was leveled and inmates and staff perished. Traces of the foundation are all that remain today.

Air raid shelters near Ground Zero offered a little protection. While most people within three-tenths of a mile of the hypocenter died instantly, some of those inside these shelters survived the initial blast. After the war, the US military studied the construction of the shelters and the locations of the survivors and the dead. This information was believed to have been gathered for the possible building of nuclear shelters for future wars.

A statue of a mother and her dying baby outside the Nagasaki Museum has a plaque noting the time and date of the atomic bomb explosion.

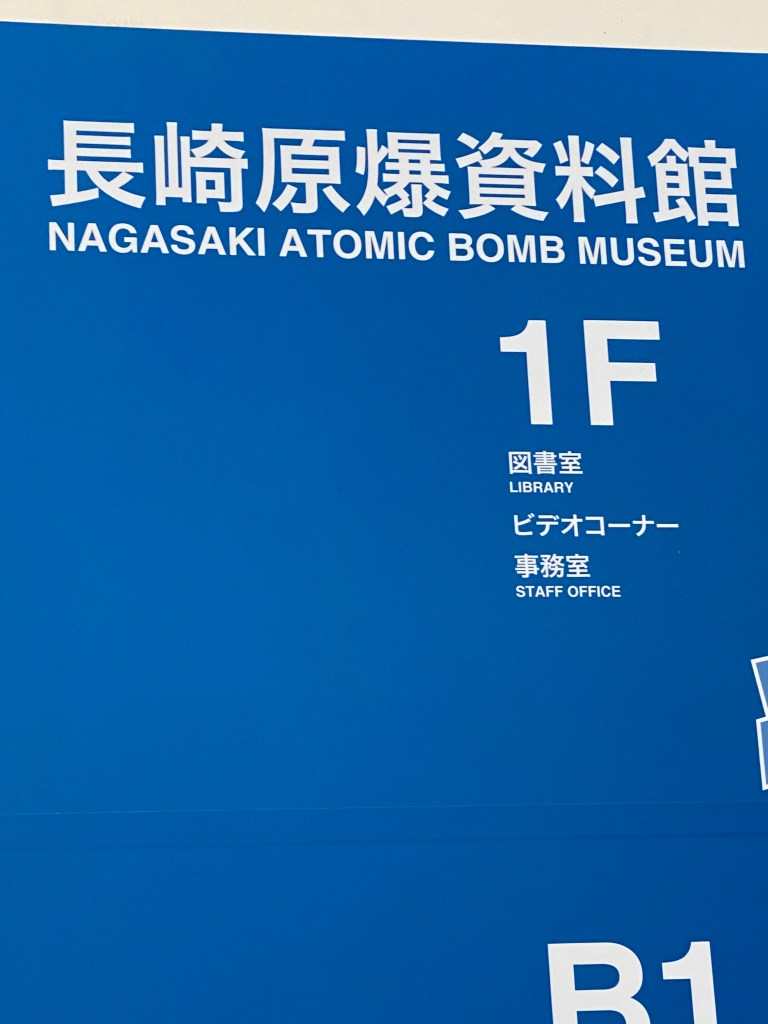

The Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum was similar to the one in Hiroshima. Again, there was a clock stopped at the exact moment of the detonation of the bomb, this time 11:02.

The chronology of events leading up to the use of the atomic bomb in Nagasaki is chilling. I didn’t know Nagasaki was actually the back-up target that day. If only the clouds hadn’t cleared, the city might have been spared.

I found it interesting that the Japanese give a different reason for the necessity of using atomic bombs at the end of World War II. This is part of a display in the museum:

“It is said that the atomic bombs were used to hasten the end of World War II.” (Okay, that’s what I’d always thought.) “But another purpose was to display the success of the Manhattan Project, into which two billion dollars had been invested. The atomic bombings were also the first strategic move in the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union.”

Wow, the US used the bombs because we’d spent so much money developing them, and we wanted to show Russia how tough we could be?

One reason we travel is to broaden our minds, and though I might not totally agree with the words posted in the Nagasaki Peace Museum, I can respect that point of view.

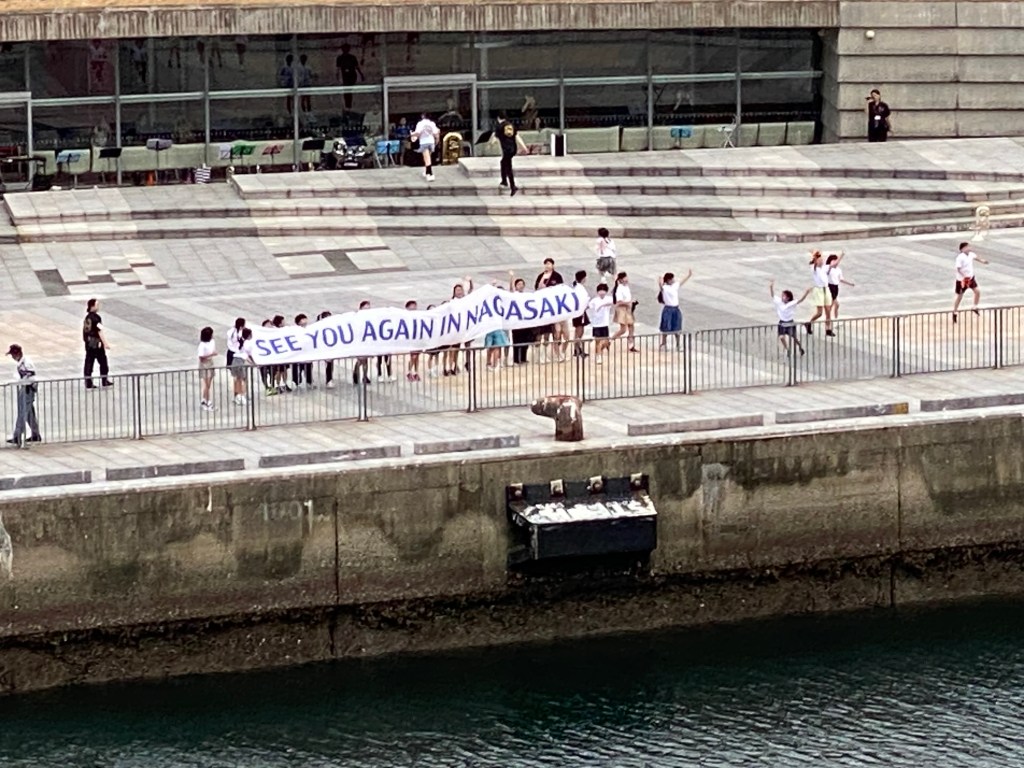

The Japanese may have once been our enemies, but there was nothing but goodwill as these youngsters gathered to bid us farewell when our boat left the harbor of Nagasaki.